From Taissia Basaria

01 Dec - 22 Dec 2016

The Trelex residency went above all my expectations. It was amazing to see just how productive one can be given the time to work and the right environment and Refugio has been the perfect place. I was on the residency for 3 weeks. This was the first time I had gotten a chance to focus solely on my work without other obligations. I began painting right away. My daily schedule consisted of getting up at 4 am and after a quick breakfast, I was on site painting from life. On most days by 10 am, a couple landscapes were completed and the rest of the day was spent walking the jungle and scouting out the next painting location.

Tambopata River

Even before arriving in Peru, I knew that the clay licks (colpas) where going to be one of my main subjects. They attract an abundance of wildlife and the colorful Macaw parrots flock there by the hundreds. With color being the most important element in my work, it was surreal to see such visual lushness in person and to be able to capture it in paint. But this I couldn't have done without the help of the Rainforest Expeditions guides. They were beyond generous with their time and, despite being on a tour schedule, let me paint the colpas from life. It is these paintings that I am basing my new body of work on, as I feel that it is the colpa that most embodies the spirit of the Amazon jungle with its visual abundance and the nourishment it provides.

Chuncho Colpa plein air

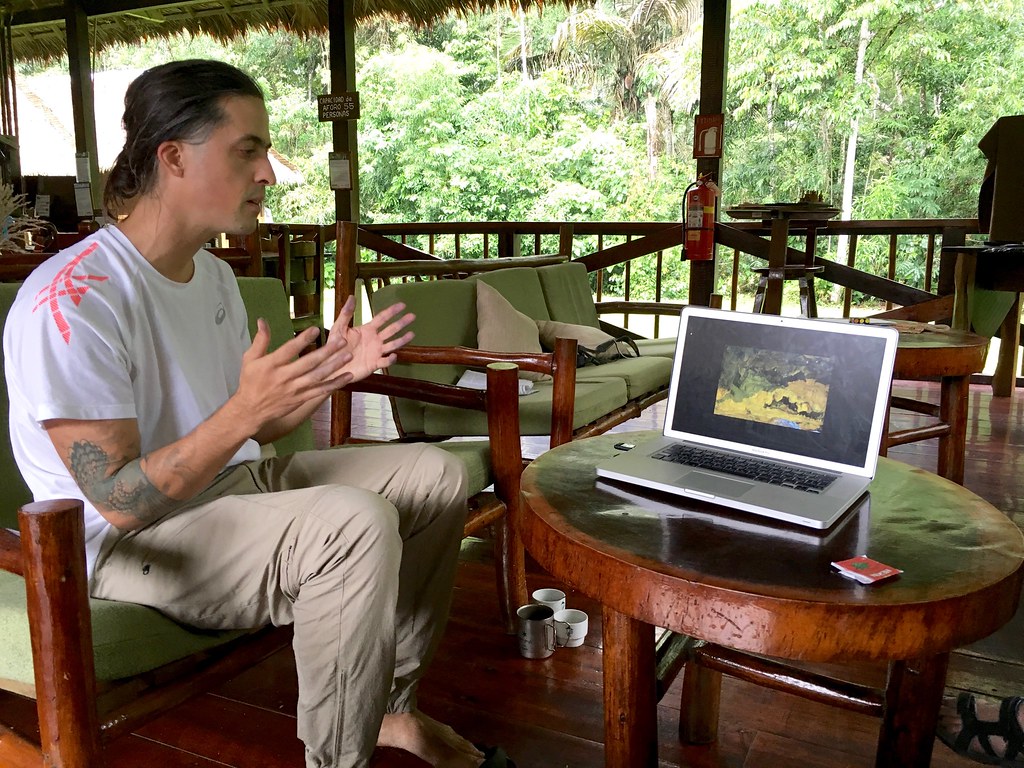

The lodge is a hot spot for career professionals from all fields. Refugio welcomes many projects and there is always something new to learn. Whether it was going on night walks to the light trap to find new species of Tiger Moths, re-releasing a baby snake after its photo shoot for a biology book or watching a drone film uncharted jungle canopy. The jungle not only supplied subject matter but also a nurturing work environment to create.

At the tower, taken with a drone

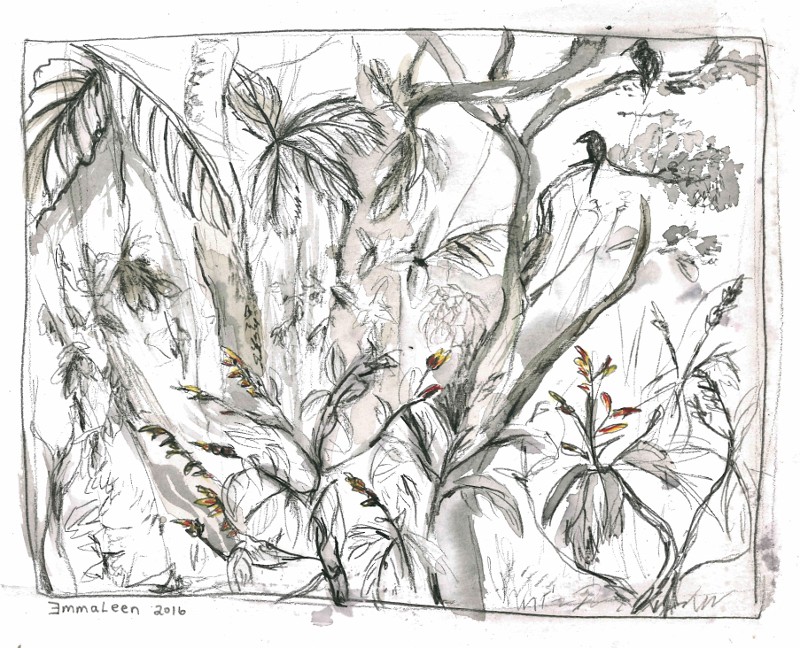

I was very fortunate that my stay coincided with fellow artists Emmaleen. Although we had different styles, our works complemented each other well and I enjoyed watching her process. We spent many days drawing and walking the jungle paths together.

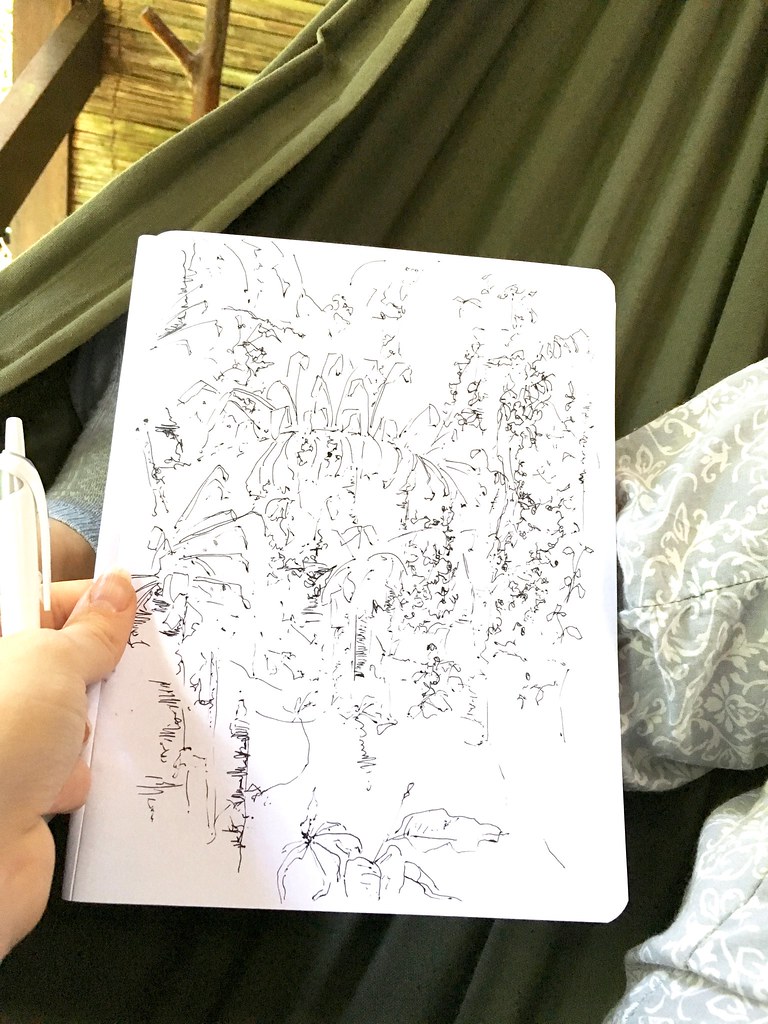

Emmaleen

The management team at Refugio were very supportive of our work and over our last week there they arranged a gallery reception for us (pictures of the opening below). The work from the residency filled a very long communal dining table. After dinner guests and lodge staff got to finally see what we were working on over the past month. It brought me a lot of joy seeing everyone examining the works and trying to decide which one was their favorite. Many recognized the places I painted and we stayed up late as the employees told stories about the giant Lupuna tree from my drawing or about how they could tell the exact time of day that I had painted the river. Upon my return home, I found that it was the people that I missed the most.

Gallery opening night

Trelex residency was a once in a lifetime experience. I still find it hard to believe that this opportunity came into my life. Working in the field challenged by painting abilities and the works completed while at the residency have already begun to open doors for me back home. Again, thank you Nina, for your generosity in creating such projects for fellow artists and Abi for all the care and support.

Colpa, painted from sketches done in the Amazon

|

| Tambopata River |

Even before arriving in Peru, I knew that the clay licks (colpas) where going to be one of my main subjects. They attract an abundance of wildlife and the colorful Macaw parrots flock there by the hundreds. With color being the most important element in my work, it was surreal to see such visual lushness in person and to be able to capture it in paint. But this I couldn't have done without the help of the Rainforest Expeditions guides. They were beyond generous with their time and, despite being on a tour schedule, let me paint the colpas from life. It is these paintings that I am basing my new body of work on, as I feel that it is the colpa that most embodies the spirit of the Amazon jungle with its visual abundance and the nourishment it provides.

|

| Chuncho Colpa plein air |

The lodge is a hot spot for career professionals from all fields. Refugio welcomes many projects and there is always something new to learn. Whether it was going on night walks to the light trap to find new species of Tiger Moths, re-releasing a baby snake after its photo shoot for a biology book or watching a drone film uncharted jungle canopy. The jungle not only supplied subject matter but also a nurturing work environment to create.

|

| At the tower, taken with a drone |

I was very fortunate that my stay coincided with fellow artists Emmaleen. Although we had different styles, our works complemented each other well and I enjoyed watching her process. We spent many days drawing and walking the jungle paths together.

|

| Emmaleen |

The management team at Refugio were very supportive of our work and over our last week there they arranged a gallery reception for us (pictures of the opening below). The work from the residency filled a very long communal dining table. After dinner guests and lodge staff got to finally see what we were working on over the past month. It brought me a lot of joy seeing everyone examining the works and trying to decide which one was their favorite. Many recognized the places I painted and we stayed up late as the employees told stories about the giant Lupuna tree from my drawing or about how they could tell the exact time of day that I had painted the river. Upon my return home, I found that it was the people that I missed the most.

|

| Gallery opening night |

Trelex residency was a once in a lifetime experience. I still find it hard to believe that this opportunity came into my life. Working in the field challenged by painting abilities and the works completed while at the residency have already begun to open doors for me back home. Again, thank you Nina, for your generosity in creating such projects for fellow artists and Abi for all the care and support.

|

| Colpa, painted from sketches done in the Amazon |

From Emmaleen Tomalin

01 Nov - 21 Dec 2016

A pair of slinky snake- like tayras weaving their way.

Old man baby- faced capuchins with tails dipped in foam snatching fruits just outside my room.

Bear faced tamarins and elfin squirrel monkeys moving across the canopy.

Tiger moths and a purple berry dragonfly,

Bullet ants hunting on the outskirts.

Beastly, foul smelling peccaries with their squealing young. Clicking their teeth and bristling their hair.

I heard footsteps and felt eyes on me.

Mocking wild turkeys and a nightly moaning bamboo rat.

A silent, slivery blue jungle bathed in super moon light.

Gorgeous snowflake daisy fungi,

Curly tails and swirly twigs. Walking trees growing new limbs.

A stripy tailed raccoon weasel creature straight out a story book.

Pulsing azure blue morpho butterflies,

A gentle two-toed sloth person combing her hair in a world time all of her own.

Crashing trees, drowning darkness and firefly fairies.

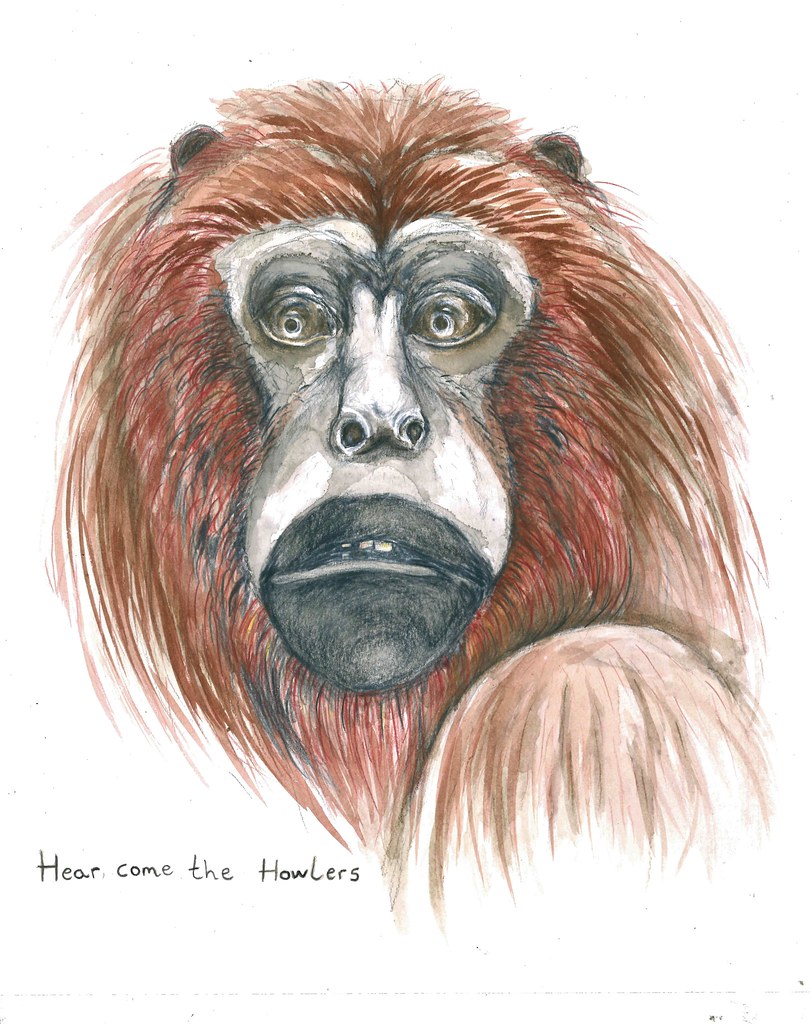

Slow mournful ginger howlers resting and tuning up. And the eerie echoing begins. Here come the howlers.

There were times when being in the amazon felt like an out of body altered mind experience. I lived in a surreal dream world for seven weeks, with extremely heightened emotions, punctuated by reality from members of my own species. I was lucky enough to spend time both at the Tambopata research centre and Refugio Amazonas.

Everything was stranger and more complex than my wildest imaginings. How does an artist even begin to capture a place like this? I wondered. I knew I had to start scribbling as soon as possible before fear kicked in.

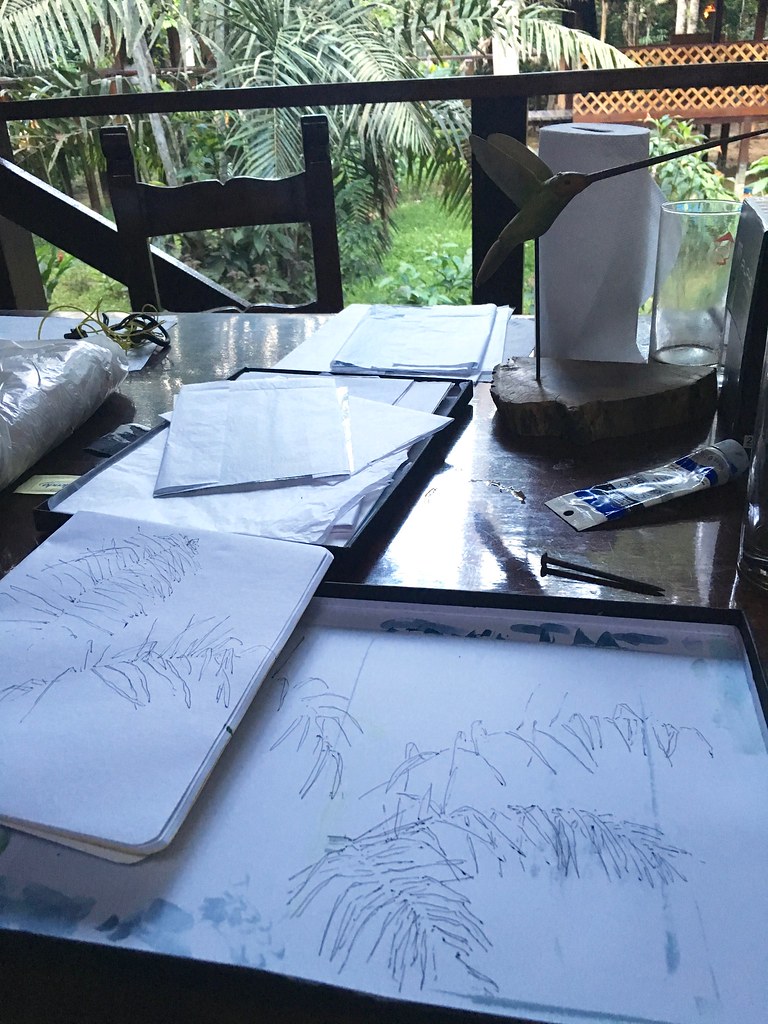

I began working in a sketchbook taking as many visual notes as possible and was fortunate enough to draw some animals from life. My absolute favourites were the two toed sloth and the howler monkeys. It was such a privilege to see these incredible animals let alone draw them. Although drawing through a telescope proved to be tricky.

I soon learned how difficult it is to see animals and how active of a process it is to spot them. The jungle slowly reveals itself if you are quiet, open minded and alert. I really enjoyed the daily visits from the macaws and peccaries and spent a lot of time trying to draw them in movement. Later on I started drawing hybrids of animals and began my own imaginary menagerie.

I slowed down in my last two weeks and spent a lot of time staring at trees, walking around on my own and trying to listen closely to the voices in the jungle. I enjoyed swinging on a hammock in the middle of the night watching the firefly fairies dart around in the enveloping darkness. This quiet absorption thinking time was just as important to me as drawing.

I saw and felt so much in the jungle and I am eternally grateful to have had this experience and to come home with countless ideas and invaluable visual information for new picture books.

I’m thankful I got to share my residency with the gentle, light-footed poet Isabel Galleymore who braved illness and the tough-as-nails landscape artist Taissia Basaira who grew a little pale but didn’t bat an eyelid after being repeatedly stung by a bullet ant. I’m also so glad I met the wholesome soul Laura Macedo (the guest service manager at TRC) who listened to me play guitar in the evenings. I learnt so much from these three women who challenged me each in their own way. I would also like to thank all the guides and rainforest expeditions for housing us and looking after us. Nina, thank you for starting such an amazing residency, Abi, thank you for all the leg work.

Emmaleen Tomalin's Flickr Album

A pair of slinky snake- like tayras weaving their way.

Old man baby- faced capuchins with tails dipped in foam snatching fruits just outside my room.

Bear faced tamarins and elfin squirrel monkeys moving across the canopy.

Tiger moths and a purple berry dragonfly,

Bullet ants hunting on the outskirts.

Beastly, foul smelling peccaries with their squealing young. Clicking their teeth and bristling their hair.

I heard footsteps and felt eyes on me.

Mocking wild turkeys and a nightly moaning bamboo rat.

A silent, slivery blue jungle bathed in super moon light.

Gorgeous snowflake daisy fungi,

Curly tails and swirly twigs. Walking trees growing new limbs.

A stripy tailed raccoon weasel creature straight out a story book.

Pulsing azure blue morpho butterflies,

A gentle two-toed sloth person combing her hair in a world time all of her own.

Crashing trees, drowning darkness and firefly fairies.

Slow mournful ginger howlers resting and tuning up. And the eerie echoing begins. Here come the howlers.

There were times when being in the amazon felt like an out of body altered mind experience. I lived in a surreal dream world for seven weeks, with extremely heightened emotions, punctuated by reality from members of my own species. I was lucky enough to spend time both at the Tambopata research centre and Refugio Amazonas.

Everything was stranger and more complex than my wildest imaginings. How does an artist even begin to capture a place like this? I wondered. I knew I had to start scribbling as soon as possible before fear kicked in.

I began working in a sketchbook taking as many visual notes as possible and was fortunate enough to draw some animals from life. My absolute favourites were the two toed sloth and the howler monkeys. It was such a privilege to see these incredible animals let alone draw them. Although drawing through a telescope proved to be tricky.

I soon learned how difficult it is to see animals and how active of a process it is to spot them. The jungle slowly reveals itself if you are quiet, open minded and alert. I really enjoyed the daily visits from the macaws and peccaries and spent a lot of time trying to draw them in movement. Later on I started drawing hybrids of animals and began my own imaginary menagerie.

I slowed down in my last two weeks and spent a lot of time staring at trees, walking around on my own and trying to listen closely to the voices in the jungle. I enjoyed swinging on a hammock in the middle of the night watching the firefly fairies dart around in the enveloping darkness. This quiet absorption thinking time was just as important to me as drawing.

I saw and felt so much in the jungle and I am eternally grateful to have had this experience and to come home with countless ideas and invaluable visual information for new picture books.

I’m thankful I got to share my residency with the gentle, light-footed poet Isabel Galleymore who braved illness and the tough-as-nails landscape artist Taissia Basaira who grew a little pale but didn’t bat an eyelid after being repeatedly stung by a bullet ant. I’m also so glad I met the wholesome soul Laura Macedo (the guest service manager at TRC) who listened to me play guitar in the evenings. I learnt so much from these three women who challenged me each in their own way. I would also like to thank all the guides and rainforest expeditions for housing us and looking after us. Nina, thank you for starting such an amazing residency, Abi, thank you for all the leg work.

Emmaleen Tomalin's Flickr Album

100 Artists

As Hugo Yoshikawa arrives this afternoon, Trelex welcomes its 100th Artist in Residence. To celebrate we have mapped out all 100 artists, showing roughly where everyone has arrived from. I’m honored to have welcomed so many artists from all these many places into both my studio at Trelex and the rainforest of Peru at Trelex Amazonas. Hover or click on the dots for information on each artist. [full screen]

Leaf Portraits by Alina Dolgin

Work by one of our first Trelex Amazonas residents, Alina Dolgin, inspired by her time in the Peruvian Rainforest.

From Ben & Sally & Yuri

01.03.2016 - 31.03.2016

Trelex Amazonas Residency: An Olfactory Exploration of Place.

Lai/Moat – March 2016

From Puerto Maldonado the Chloropotera navigated the swollen Rio Tambopata southwestwards, upstream against the current and towards the distant Andean sierra. We passed flood-devastated plantations of banana and papaya and caught sight of distant clandestine miners feverishly labouring in search golden particulates with improvised, silt-sifting mechanisms. Then our first acquaintance with those which would become a constant during the weeks ahead; the howlers and capuchins, guacamayos, palms, vines, palo balsa, cana brava, unidentifiable merging vegetation straining upwards to the solitary, majestic Bertholletia exelsa (radium-emitting, they tell us). And then we’re engulfed in darkness and primary rainforest. Tambopata de verdad, immediate sensory overload and a welcome of open hearts, laughter and cool flannels from the Rainforest Expeditions community.

|

| Rio Tambopata |

During those early days we floated between a conflicting world of jungle opulence and violence, observing a smattering of enthusiastic, long-lens tourists in virgin permethrin-impregnated shirts and a community of dedicated researchers – some of whom appeared to be assimilating the characteristics of their subjects; long limbs, flickering eyelids, heightened nocturnal animation.

We followed dark paths that meandered to nowhere and traversed the haunted lake. We shifted our gaze skyward following the mid-morning trajectory of the snake-like Anhinga bird to the canopy and beyond and then deep into the soil to the tangle of roots and mineral deposits. With our senses pre-conditioned by decades of exposure to European temperate familiarity, the expectation was of a scented bombardment – an exotica emanating from kaleidoscopic vegetation: floral, pollen, nectar, the sweet and the seductive. We searched with our noses and encountered damp, decaying ambiguity, decomposition, muted and transient micro-fragments originating from distant, anonymous sources. In his commendable work, ‘Tropical Nature’, Forsyth (1984) offers us a succinct explanation for this:

“Tropical plants avoid wind pollination because this scattershot method of gene dispersal is effective only if there are lots of targets nearby. Since there will probably be few individuals of the same species nearby, a plant casting its genetic fate to the wind faces a high risk of losing its investment”

Thus the impetus of our emerging inquiry now focused on what lay beneath. For this we’d adapt new exploratory techniques gleaned from a revelatory field trip with leading rainforest scientist Dr.Varun Swamy: in-depth genus identification, rubbing, scoring, snapping, pulverizing, peeling any potentially scented material. We followed clues found in a fading photocopy of Gentry’s Field Guide to the Families and Genera of Woody Plants. We immersed in extended conversations with those that had an intimate knowledge of the rainforest through a lifetime of close contact – the chefs, porters, guides, members of the Infierno community – all generous with their wisdom, revealing personal botanical perspectives shared in a gentle vernacular. With our improvised apprenticeship now complete we were ready to fully immerse in the intoxicating neotropical world of aromatic possibility.

Our initial forays yielded encounters with fast-flowing latex, rancid M.citrifolia (with apparent life-prolonging properties), barks of stale garlic, the sour odour of the Pluthereum (identifiable by the ant community that reside within its stems prior to castrating the host to prevent flowering in order to reinforce the stem structures) and the Aniba with its urgent turpentine-esque tone. The proximity to our subjects was not entirely without risk – on more than one occasion we were injected with a searing toxic alkaloid delivered with stealth and guile by the Pseudomyrmex dendoicus. An identical alkaloid has been used in Ese Eja communities to castigate those partaking in misadventures of infidelity.

|

| Aniba Leaf |

|

| Unknown Funghi |

The jungle kitchen was alive with industrious activity. Food and associated provision had to be transported upstream by boat, overloaded carts heroically hauled through the rainforest, stored, prepared, presented, consumed, cleared, cleaned - herculean tasks deserving of universal admiration. We noticed a rare lull in activity during the early afternoons due to the religiously observed football game (participation encouraged). The head chef granted us access to the kitchen during this time for the purpose of ‘the advancement of artistic research’. We found heat and ice (scant supplies due electricity rationing), pitted and bruised steel saucepans and metallic bowls of varying sizes. Collectively these components created a rudimentary, yet effective distillation system capable of facilitating the infusion and suspension of aromatic molecules within water. With basic chemistry and infinite organic source material we’d be able to capture olfactory representations of the rainforest in the form of hydrosols.

Our selection methodology involved collecting samples from top to bottom - high canopy to sub-rainforest floor. Motivated in equal measure by material diversity, olfactory output and narrative potential the following samples were collected (with the support of researchers and volunteers) and converted into hydrosols:

- Guacamayo nest substrate - mixed mineral/vegetation (29m)

- Philodendrum spp. - flower/leaf (18m)

- Banisteriopsis Caapi - vine (15.4m)

- Uristigma Matapalo – bark (15m)

- Spondias Mombin/Ubo - Fruit (0m/9m)

- Piper – leaf (4.8m)

- Aniba Rosodora – leaf (4.4m)

- Theobroma Cacao – fruit (3.8m)

- Citrus Reticulata – Leaf (3.2m)

- Theobroma grandiflorum/Copazu – fruit (2.7m)

- Urera Baccifera – leaf (2.2m)

- Croton lecheri/Sangre de Grado – bark/sap (2m)

- Cotton T-shirt/3 days unwashed – fabric (1.6m)

- M.Citrifolia/Noni – fruit (1.4m)

- Floresta Super Extremo – chemical (1.2m)

- Gallersia Integrifolia/Ajosquiro – bark (0.8m)

- Unknown Funghi (awaiting identification) (0m)

- Collpa Claylick clay (mineral) (-7m)

- Rio Tambopata water (- 9m)

(figure in brackets denotes sample distance in meters from rainforest floor)

|

| Collpa Claylick Clay |

The collection from Tambopata represents the initial stage of an evolving project, a work in progress. The aromas we carry with us are transient, temporary - some gradually fading as a result of time, fluctuations in temperature and altitude. Others will maintain their vigour.

Our journey will now take us onwards to the Altiplano, Atacama, Atlantic and beyond where new narratives will emerge and the distillation process will continue. And as we leave the jungle we learn that a hydrosol laboratory will be developed to become a permanent resource at Rainforest Expeditions.

|

| Completed Hydrosols |

Our gratitude and thanks go to:

Kurt Holle, Nina Rodin, Abi Box, Milagros Saux, Jesus Duran, Dr.Varun Swamy, Katherine Torres, Julian Herrera Sara, Claudia Torres Sovero, Patricia Deza, Richard Vargas Jara, Liz Paipay, Clifton Carter, Jesse Beck, Sabino Quispe Jaen, Cesar Carrasco Moroco, Eric Franz, The Hval Family, Misael Valera, Danny Couceiro, Lana Austin, Jorge, Tony, Dino.

From Sophie Morrish

29.02.2016 - 31.03.2016

Happiness doubled by wonder *

(Part One)

The Tambopata Rain Forest inspired in me a powerful reconnection with a particular state of innocence, one of intense childlike wonder. Overwhelmed by the sensorial clamour of the place, the heat, humidity, sounds and smells, all unfamiliar, all enthralling, not least among them was the sheer visual complexity of the jungle. Looking about you it is difficult to settle your gaze on any one thing, the rich tangle of shrubs, trees and vines, far from being a passive backdrop, is host to a myriad of wonders and innumerable narratives that play out to an intricate soundtrack of birds, insects, monkeys and frogs, mostly unseen, their presence betrayed only by their sounds.

Perception is radically different here to that experienced in a tamed landscape, it is an environment of vital forces, a near pristine habitat of living systems that are evident at every turn, (Tambopata National Reserve is one of the largest contiguous areas of primary rainforest in the Amazon basin and considered by many to be the best). Walking in the forest new and intriguing natural phenomena assail you at every turn; to realise a singular viewpoint or focus is impossible and perhaps more importantly, seems senseless to pursue. Very quickly a strong sense of being ‘within’ takes hold and, surrounded, you realise your perspective is rarely one of any great (physical), distance from a thing observed.

It takes time to feel your way into this place, as initial fears and uncertainties slowly fall away - although never entirely - they are replaced by transient sensations of ease, familiarity, comfort and most frequently, elation. Days are punctuated in unanticipated ways - the distant sound of a large tree crashing to the forest floor, the chatter of monkeys, call and response between Toucan, the grunting, crunching and snorting of a passing band of White-lipped Peccaries, (not to mention their eye wateringly pungent odour!), the relentless flow of industrious leafcutter ants across the forest floor, all are fascinating, all are utterly absorbing. Once you stop to observe a given phenomena you become aware of all the surrounding relationships that give context to that which first caught your attention. Hours pass in what seem like minutes, the days never long enough to exhaust the feeling of enthrallment. It is the complex living connections, visceral and dramatic that are in essence the magic of the place. Here it is possible to feel deeply, what we, (in the ‘developed world’), have lost by all we have gained.

Returning home from the jungle, there is so much to process, so many impressions and experiences, thoughts, feelings and ideas. Reading through my notebooks, looking at photographs, films and drawings made, listening to numerous field recordings, it feels too soon…a sharp pang of emotion, a sense of loss even, tells me it is indeed too soon for me to acknowledge this experience as passed, (past).

My starting point for this residency was to explore unlikely parallels that might be drawn between my ‘habitat’, North Uist, in the Western Isles of Scotland, (arguably one of the most Bio-diverse places in the U.K.), and that of the Amazon Rain Forest, (the most Bio-diverse area of the planet); locations whose natural circumstances could hardly be more different but each of whom is of immeasurable value in their own right and should I feel, be acknowledged and treated as such. This particular strand of enquiry, (a component of other deeply held, long standing creative interests), began with field recordings made in Uist in early 2015. Now, enriched by juxtaposition to the Amazonian ‘data’, the work needs time to develop, I am excited to see where and to what it will lead. I hope I can do justice to all that has brought me thus far.

For an artist whose work primarily stems from walking and consideration of phenomenal relationships, a visit to the Amazon Rain forest was nothing short of the most treasured and exquisite of gifts - one that will enrich and inform my practice far into the future, one for which I do not have the words to adequately express my gratitude for. I am eternally grateful to Nina Rodin and The Trélex Residency for this wonderful opportunity and to Kurt Holle / Rain Forest Expeditions for their unstinting, remarkable generosity in facilitating it. Equal thanks go to all the hardworking staff at the Refugio and Tambopata Research lodges, to the guides and researchers whose knowledge, expertise and good humour added so greatly to the whole experience. Thanks goes too to the many visitors who took a keen interest in my work and who welcomed me to join their walks, in particular Edith Wu, Lynette McLamb & Todd Steiner, with whom, (in the company of Robin their guide), I saw so many marvellous creatures.

I am grateful also to CNES (Western Isles Council) and Creative Scotland for the Visual Arts Grant that supported my residency and last but by no means least, to my partner René Jansen, for his encouragement and support and for holding the fort and walking the dogs in my absence – I couldn’t have done it without you.

Sophie Morrish

North Uist, April 2016

G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936)

From Ella Dawn McGeough

01.01.2016 - 30.03.2016

and, something like fire dancing: Amy Brener, Patrick Cruz, Barbara Kasten, Scott Lyall

Last winter, I spent 87 days on residency in the southwest corner of Peru in the Tambopata National Reserve, an area acclaimed for having the planet’s densest bio-diversity. I brought Public 51 edited by Scott Lyall and Christine Davis on the subject of colour with extensive writing by Isabelle Stengers. While I was preparing to leave Toronto, I was in the early stages of planning this exhibition. With the upcoming limits of communication, I sent preliminary invitations to four artists: Amy Brener, Patrick Cruz, Scott Lyall, and Barbara Kasten. With the exhibition plan barely a sketch, their agreement was a performance of trust.

Initially, what held these artists’ practices together was a question of diffusion: an investment in the stuff of transparency and lightness, whether with the glazed ink and laminated glass within Scott’s works; embedded reflective elements and delicate films of silicon and resin within Amy’s sculptures; temporal quickness at play in Patrick’s unstretched canvases, where individual works act as vectors for the next; or the illuminated planes of screen and glass employed by Barbara in her sculptural sets. Despite the vitreous quality of many of their works, the layers used seemed to offer a resistance against ephemerality. Instead, each artist appeared to assert the relevance of materiality and technique. Through repetition, something light gained substance, like the weight of endurance.

The rainforest is heavy with the weight of its lightest entities: fungi…ants…butterflies. Every rainy season, for a brief duration, a parasitic plant emerges from the bark of a tree as tiny yellow fruit. Caterpillars arrive to relentlessly chew the plant, while a mass of ants stand as bodyguards to protect against would-be predators such as birds and larger insects. The ants are rewarded for their service with honeydew drummed from an exposed organ on the caterpillars’ back. When the butterfly finally presents itself, its wings blaze with an image of the yellow fruit. This image is produced without light; it is an image of home, an image of process called colour. Collectively, each entity survives in sympathy, held to the others through the dynamics of infection.

Likewise, the endurance of a work of art is either confirmed or denied by its power to infect and be infected by other artworks in both the space of exhibition and the space of history. This is not a matter of power as repression, i.e. the power of one entity to impose itself upon a lesser entity. Rather, the term infection is used as a matter of inciting an embodied relationship. What Stengers’ describes as the link between power and adventure. Effectively, the power of one being is gained by its ability to be receptive to the power of another being. The conceit of this exhibition is that―like interspecies relationships evident in nature―that which endures in culture is not self-sufficient. However while in nature, material reality holds subjects together. In visual art, it is subjective reality that holds objects together. It is the visitor’s awareness that forms the non-discursive link between art objects. Held together, each work valorizes the other, shapes the other, attributes a role to the other.

Composed of a relationship between four diverse artists whose respective practices are separated by cultural context, methodology, and media, the exhibition becomes a type of portrayal with the artworks loosely mirroring the role of plant, ant, caterpillar, or butterfly. However, it is a portrait that follows the rules of mimicry over representation. On the wall, Barbara’s work assumes the twinned roles of host and guest, both here and there. It is both a convergence of relational activities that belong to the studio―a space of becoming―and a photographic result intended for visual consumption. Amy’s Flexi-Shield series are suspended from the ceiling: talismanic dresses made from poured silicone whose slippery interface contains tools for survival. Hung in repetition, they function as equipment. A polymorphous defence system. Patrick’s installation eschews permanence in favour of dispersion. Laid on the ground, his improvisational canvases slowly secrete, transferring to the soles of shoes. Upstairs, Scott pursues his reflection into the gap of historical difference between painting and photography. Specifically the role of colour within these two modes of artistic expression as an eternal object that comes when called, that appears when wanted. Colour that matters.

Initially, what held these artists’ practices together was a question of diffusion: an investment in the stuff of transparency and lightness, whether with the glazed ink and laminated glass within Scott’s works; embedded reflective elements and delicate films of silicon and resin within Amy’s sculptures; temporal quickness at play in Patrick’s unstretched canvases, where individual works act as vectors for the next; or the illuminated planes of screen and glass employed by Barbara in her sculptural sets. Despite the vitreous quality of many of their works, the layers used seemed to offer a resistance against ephemerality. Instead, each artist appeared to assert the relevance of materiality and technique. Through repetition, something light gained substance, like the weight of endurance.

The rainforest is heavy with the weight of its lightest entities: fungi…ants…butterflies. Every rainy season, for a brief duration, a parasitic plant emerges from the bark of a tree as tiny yellow fruit. Caterpillars arrive to relentlessly chew the plant, while a mass of ants stand as bodyguards to protect against would-be predators such as birds and larger insects. The ants are rewarded for their service with honeydew drummed from an exposed organ on the caterpillars’ back. When the butterfly finally presents itself, its wings blaze with an image of the yellow fruit. This image is produced without light; it is an image of home, an image of process called colour. Collectively, each entity survives in sympathy, held to the others through the dynamics of infection.

Likewise, the endurance of a work of art is either confirmed or denied by its power to infect and be infected by other artworks in both the space of exhibition and the space of history. This is not a matter of power as repression, i.e. the power of one entity to impose itself upon a lesser entity. Rather, the term infection is used as a matter of inciting an embodied relationship. What Stengers’ describes as the link between power and adventure. Effectively, the power of one being is gained by its ability to be receptive to the power of another being. The conceit of this exhibition is that―like interspecies relationships evident in nature―that which endures in culture is not self-sufficient. However while in nature, material reality holds subjects together. In visual art, it is subjective reality that holds objects together. It is the visitor’s awareness that forms the non-discursive link between art objects. Held together, each work valorizes the other, shapes the other, attributes a role to the other.

Composed of a relationship between four diverse artists whose respective practices are separated by cultural context, methodology, and media, the exhibition becomes a type of portrayal with the artworks loosely mirroring the role of plant, ant, caterpillar, or butterfly. However, it is a portrait that follows the rules of mimicry over representation. On the wall, Barbara’s work assumes the twinned roles of host and guest, both here and there. It is both a convergence of relational activities that belong to the studio―a space of becoming―and a photographic result intended for visual consumption. Amy’s Flexi-Shield series are suspended from the ceiling: talismanic dresses made from poured silicone whose slippery interface contains tools for survival. Hung in repetition, they function as equipment. A polymorphous defence system. Patrick’s installation eschews permanence in favour of dispersion. Laid on the ground, his improvisational canvases slowly secrete, transferring to the soles of shoes. Upstairs, Scott pursues his reflection into the gap of historical difference between painting and photography. Specifically the role of colour within these two modes of artistic expression as an eternal object that comes when called, that appears when wanted. Colour that matters.

installation view, and, something like fire dancing, 2016

Barbara Kasten, Studio Construct 19, 2007

Patrick Cruz, landscape painting version 4, 2013-16

Amy Brener, Flexi-Shield (sunset), 2016; Flexi-Shield (amulet), 2016; Flexi-Shield (sunrise), 2016

installation view upstairs, and, something like fire dancing, 2016

Scott Lyall, detail view (untitled) redshift, 2016

Photo Credit: Toni Hafkenscheid, Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto

Mystery of the Yellow Bulbs: Discovery in the Amazon of a New Caterpillar-Ant-Parasitic Plant Relationship by Aaron Pomerantz

Public 51: Colour, edited by Christine Davis and Scott Lyall

FrameWork 9/16: Aryen Hoekstra on and, something like fire dancing

Ella's website

From Abi Box

01 - 10 Jan 2016

My time in the rainforest has made me want to write poetically but I’m a terrible poet. I'll start by running up a long list of disconnected adjectives like wild, unruly and tangled, alive, darker than I imagined, damp, dirty, close,.. until we climbed up the tower.

Looking out at the top of the tower, a manmade structure built to stand above the canopy, above all the mess and disorder lower down, you can see the surface of the tree tops, which look like broccoli, miles of broccoli.

|

| top of the canopy |

Climbing up through the argument of branches into the clearing feels like swimming underwater then surfacing into calm and open air. I climbed the tower three times during our visit, going at different times in the day: once in the morning to watch the light arrive, once in the evening where we watched the sun go down and another time, late at night when there was no light at all apart from the stars which littered the dark space like dust.

|

| the pond #5am |

|

| Squirrel Monkey |

I also love squirrel monkeys now. I won’t go on but I want to be one.

|

| Nina and I looking up at Howler Monkeys |

I have dived right in here, there’s so much to write about., a bit about how I came to be here. The Trélex Amazon Artist Residency was set up in 2014, a conversation happened between Nina (founder of the Trélex Residency in Switzerland) and Kurt Holle (owner of Rainforest Expeditions) and subsequently artists began arriving at the lodges to stay as residents. Two artists can come at a time during the rainy season, while there are spare rooms available, and so far eleven artists have visited. A success story but it all happened so quickly. We went out to talk in person to all the staff, guides, researchers to share our thanks and to highlight why and how much of a difference this opportunity makes to all the artists.

|

| Colin taking about his practice |

We were also able to spend time with the artists who were residents at the time, Ella, Colin and Maisie. Over the course of the week we all took it in turns to do a short talk about our our work and our interests. At Nina’s studio in Trélex, home to the first residency, she usually tries to do this in the first few days of an artist's visit, to kick start a conversation which will most likely continue throughout all the tea and coffee breaks to follow. I’m always surprised by how much stuff is unearthed when we do this, what ideas and inspirations are making people tick.

|

| Fernando and Nina walking |

Halfway through the trip I was taken aback to realise how much of a daily routine we had picked up. One full of walking and exploring; I don’t think I thought that we would do so much of it. Each walk we went on was at least a couple of hours and we often went on more than one; I was back in the girl guides. The trip to the second lodge TRC, involves a six or seven hour boat ride. Having looked at the area on Google Maps before we set off to Peru, I had a good picture of what we might look like from up above as tiny GPS dots amidst the sea of green. It was an awesome feeling to know that on each walk we took, the forest surrounding us was never ending.

|

| dramatic atmosphere |

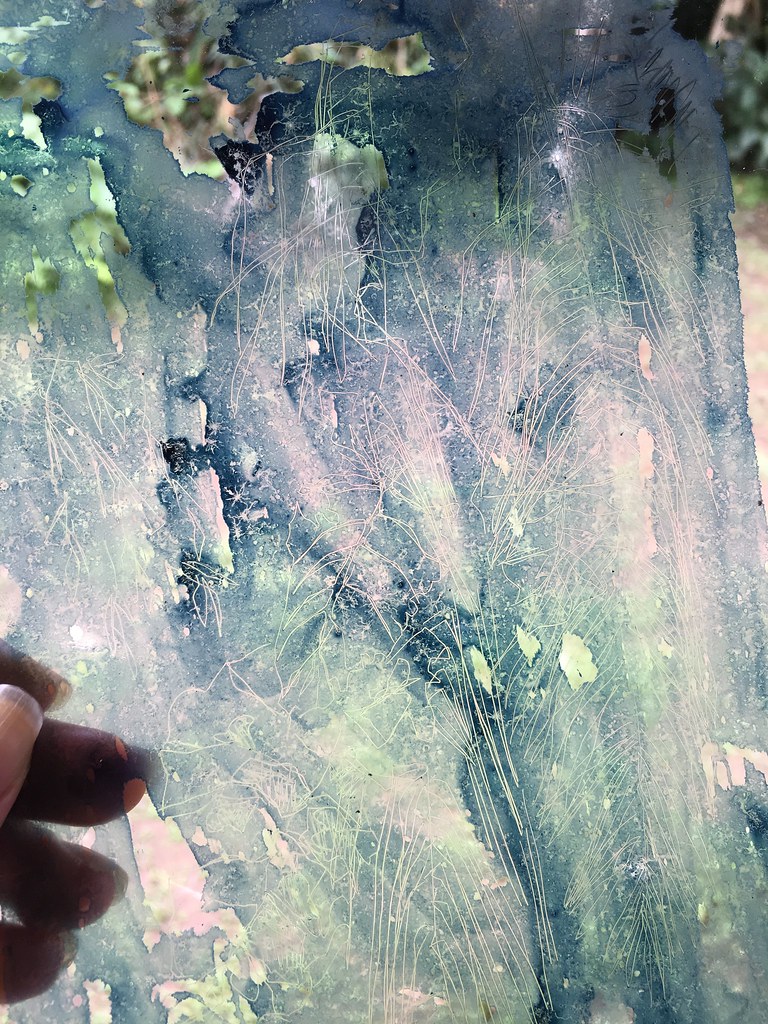

I found a fascination with a lot of things in the rainforest but the thing which kept catching my attention was the way distances appeared. An interesting sense of depth is created by the humidity, the moisture in the air obscuring anything which lies a short distance away. Tree filled backdrops are muted and misty creating an incredibly theatrical atmosphere. Especially in the mornings, along with the howler monkeys eerily sounding off their territory, it often felt like a movie set.

This unusual sense for depth was the thing I felt I could focus on within my work. My painting has a lot to do with layering and the way things take up space, or not. I found it difficult to work on anything which would portray all of this during the trip so I stuck to collecting my thoughts, taking photographs and making drawings… visual notes, of everything around me to take back to work on in the studio, back at home in London.

|

| perspex sheet etched into with a nail.. |

|

| ..held up against the rainforest |

|

| drawing the view from the lodge |

|

| Nina and I take over one of the dining tables |

Thank you to everyone at Rainforest Expeditions for making this a thing.

abi-box.com

Postcard to Fernando (our guide): “To the best pigmy owl impersonator in town. Thank you for taking me and Nina on walks, teaching us what not to touch, how best to cook fish in bamboo and how to milk a Capybara. I will never forget looking up at the stars! At Jupiter and the milky way. I cross my fingers that I am able to return soon and that you can read my handwriting! Abi xx”

|

| All Lovers Must, Abi Box |

|

| An Argument of Branches II, Abi Box |

|

| Jungle Spatula, Abi Box |

|

| Losing Ourselves Together, Abi Box |

|

| An Argument of Branches, Abi Box |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)