2 - 23 Dec 2017

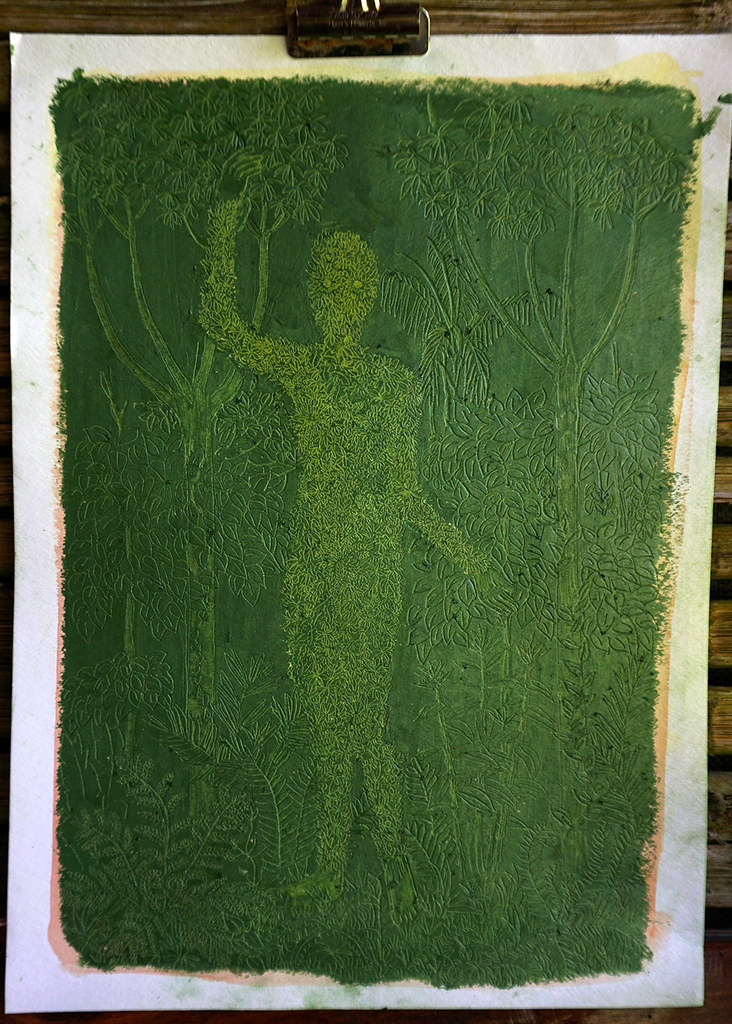

In my work often I investigate violence behind the virtue. I am interested in socio-political and moral structures that are abusive but are presented as noble. Being in the jungle I started to pay attention how those mechanisms are applied in nature. On my first trip into the jungle I was introduced to the strangler fig - a plant that kill trees and takes their shape and place. It starts growing from a small seed in a canopy several meters above the ground deposited there by a bird or animal, and it grows its roots down to the ground, in a seemingly delicate and gentle manner around the tree. It’s only when it reaches the forest floor that the strangler fig swells to engulf its host. Eventually it will kill the host tree and oftentimes hide the evidence by growing inward to fill in the gap left behind by dead and decomposed host. Its hollow inside may become a home for bats and a few creepy crawlies.

In the Tambopata rainforest there is astonishing number of insects, lizards, birds and animals that mimic something else in order to hide or attack. Some species are polymorphic - meaning the same species will come in a variety of different camouflage variations. It helps prevent predators from learning the patterns of particular camouflage. There are a different layers of disguise. For example Blue Morpho Butterfly has brown exterior wings that look like dry leaves, but when they open their wings, you’ll see spectacular, bright blue coloring. But its beauty is not to attract attention. It is a warning sign. Many species retain distasteful or poisonous chemicals acquired from their host plants make their own defences like paralyzing alkaloids, cardiac glycosides and histamines. Larvae usually acquire these chemicals, and may retain them in the adult stage. But adults can acquire them, too, by regurgitating decomposing plants containing the compounds and sucking up the fluid. Camouflage is not only visual; heat, sound, magnetism and even smell can be used to target a pray and may be intentionally concealed.

Resident biologists at Refugio Amazonas are using a light bulb to mimic a moonlight to attract and capture months for studies.

|

| The 'Theatre of Death' light trap |

The nature is endlessly fascinating but I was there as an artist not a biologist so I wanted to find an artist’s way to apprehend the jungle.

I could not see it for what it really was: a miracle. How could I experience it without all those pre-installed data?

I decided to do what babies do: explore it by mouth.

I imagined myself as an alien that has no concept of what is supposed to do with the encountered objects. I was licking plants and people and I recorded sensation that it provided but again I could only describe it by comparison to something familiar and from human perspective. The taste of frog was like slightly salted cucumber and bird was a warm, dry, old wool or flavourless sugar candy. Everything was “like” something else. At first I wanted to create a sound installation with description of the taste of the rainforest but I started to doubt the point of it since that would bring me back to the same problem that I was trying to escape.

A problem of the language itself. In his book "Violence" Slavoj Zizek explains the problem of verbal communication: "Language simplifies the designated thing, reducing it to a single feature. It dismembers the thing, destroying its organic unity, treating its parts and properties as autonomous. It inserts the thing into a field of meaning which is ultimately external to it. When we name gold "gold" we violently extract a metal from its natural texture, investing into it our dreams of wealth, power and so on, which have nothing to do with immediate reality of gold".

And then we have a hierarchy of the language. To be part of contemporary art scene artist are expected to be able to interpret their work from visual to verbal and the verbal really means English. That kind of set up allows participation in contemporary art for a certain group only and is creating a cultural class systems.

Language was always used as a tool of control and indoctrination as much as communication. Colonizers typically have imposed their language on the people they colonized, forbidding natives to speak their mother tongues. Such efforts seek the suppression and annihilation of the different ways of thinking and expression but are presented as sophistication and education.

The use of language signals certain social status and we judge accordingly. As is well known, the historical narrative is usually presented from the point of view of the conqueror. I was more interested in non-verbal, non-linear communication. I was introduced to the artworks of the Shepibo Indians, a large tribe of the Peruvian Amazon. Intricate linear geometric and symmetrical textiles and embroidery, all crafted by women, contain recursive and self-reflective motifs act as visual music maps – scores notating the chants and songs (Icaros) associated with Ayahasca healing ceremonies. The Shipibo can listen to a song or chant by looking at the designs – and inversely, paint a pattern by listening to a song or music. Indigenous mythic histories are often non-linear. They’re not necessarily chronological. They may not be concerned so much with telling exactly what happened but with the energy it conveys.

|

| Tapestry by Shepibo tribe of Peruvian Amazon |

The concept of art as a representation and was skilfully illustrated by the Belgian surrealistartist René Magritte in a number of paintings including a famous work entitled The Treachery of Images, which consists of a drawing of a pipe with the caption, Ceci n'est pas une pipe("This is not a pipe"). A more extreme literary example, the fictional diary of Tristram Shandy is so detailed that it takes the author one year to set down the events of a single day – because the map (diary) is more detailed than the territory (life), yet must fit into the territory (diary written in the course of his life), it can never be finished.

I started to observe certain marks made by insects, patterns in plants and animals and think of it as a language or a map. Maybe other animals or people can sing, feel or understand it? With our estimated 7000 different languages we haven’t translated a single spoken language of nature.

Algorithms and hidden language of nature are omnipresent and yet we dismiss it focusing on our very specific human-centric needs. I felt very disconnected from the world, I saw it as an image, a project. I wanted to feel it, connect to it, but I felt numb, detached. I decided to work with what was available to me to continue an idea of anti-gravity that I stared a year ago. I used a spider web to suspend some objects in the air but I only scared a few local people that took with for a frolic of the spirits. Then I found a small broken tree and used lianas that I wanted to believe were ayahuasca, to make it looks like the tree levitates, goes to heaven (I was thinking something along the lines of merging Amazonian shamanism and imposed Catholic believes (the ascension of Jesus and the spirits of plants). After I finished my installation I went back to the hotel to get my camera but I couldn’t find my way back to the ascending tree again. Maybe it is still there stuck in-between two worlds, maybe it fell back to the ground and was absorbed by the earthor maybe it went to heaven. I will never know.

The weather changed and most of the time it was raining now. I was observing tourists coming and going and their interactions with the local people and tourists guides. They wanted to know about their families, where did they travel, where do they live and how, if they know any shamans that would perform any rituals for them (ayahuasca being most popular). I went back to my chosen subjects of morality and culture as a camouflage for exploitation. I thought that you would not ask a tourist guide at the British Museum about his or her schooling or parents in the same way. Cheap flights and internet access opened an access to the information and travelling for people that would not have this opportunity before. Within that, like with limited edition prints or hand made objects the “authentic”, limited edition tourist experience became fetishized and ironically mass sold (Airbnb, volunteering, Ayahuasca ceremonies etc).

John Ralston Saul wrote in Voltaire’s Bastards: the Dictatorship in the West: "Tourism has become perhaps the most popular means for individuals to give themselves the sensation that they stepped outside the norm while continuing to move within it". The tourist psychology bleeds into our daily life too:we are encouraged to look but not to see, travel without discovery, think outside the box but within business context, etc. The access to travelling and information is of course regulated one way traffic: European or North American citizen is allowed and encouraged to consume the products and culture of the world but we don’t allow the same participation in exchange.

I spoke about this problem in two of my projects: Day Trippers and Made in China

Mass media created illusion of freedom and try to convert everything: spirituality, private life, religious ceremony into accessible, entertainment business. Looking for meaning, connection and nature became the biggest tourists’ attractions. We are moving from material toward cultural neo-colonialism. Slavoj Zizek calls it Capitalism with a Smiley Face. For those who practise it, it means power without responsibility and for those who suffer from it, it means exploitation without redress. In the days of old-fashioned colonialism, the imperial power had at least to explain and justify at home the actions it was taking abroad. In the colony those who served the ruling imperial power could at least look to its protection against any violent move by their opponents. With neo-colonialism neither is the case.

My time in Tambopata was running towards the end. I was disappointed with myself that I didn’t produce any tangible work which I could claim as final result of my residency, I didn’t bring back any cultural trophy from my exotic trip to the jungle. Whatever I tried to do lead me to a dead end. Maybe because I was coming from a position of a cultural explorer, an observer, an academic voyeur. Like any other tourist I didn’t create or discover but I used, explained, processed already processed, tamed and caged experience of the jungle. Only while writing this report I realised that this is my most authentic experience of artist-tourist coming back from my art residency with a maze of dead end stores, half-thoughts and unfinished objects, no answers and no successes, images and text (mine and other’s), all weaved together like Shepibo art that has no perspectives, beginnings or ends. The most authentic experience is experience of my life.

|

| Shaman's Toolbox, 2018 |